Illustration by Nikki Muller

The uproar over prominent voices being banned from social media platforms reveals a troubling—though solvable—misunderstanding of the First Amendment. From Twitter executives banning former president Donald Trump in 2021 to current Twitter CEO Elon Musk booting journalists who run afoul of his tastes, the social media outlet’s policies and moves have sparked cries of censorship and constitutional violations.

But there’s nothing illegal or unconstitutional about refusing entry to a private company’s platform. Neither of these scenarios is unlawful per the First Amendment—or even Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, a timely update addressing internet speech protection.

The term “freedom of speech,” at face value, can be misleading, as it suggests a much broader scope of legality than what the First Amendment covers. That said, poor civic education in the U.S. is a major contributing factor to this confusion over what freedom of speech really encompasses. Less than a quarter of students are proficient in civics and government, according to National Center of Education Statistics data, and the public’s trust in the U.S. government is steadily declining, according to the non-partisan Pew Research Institute.

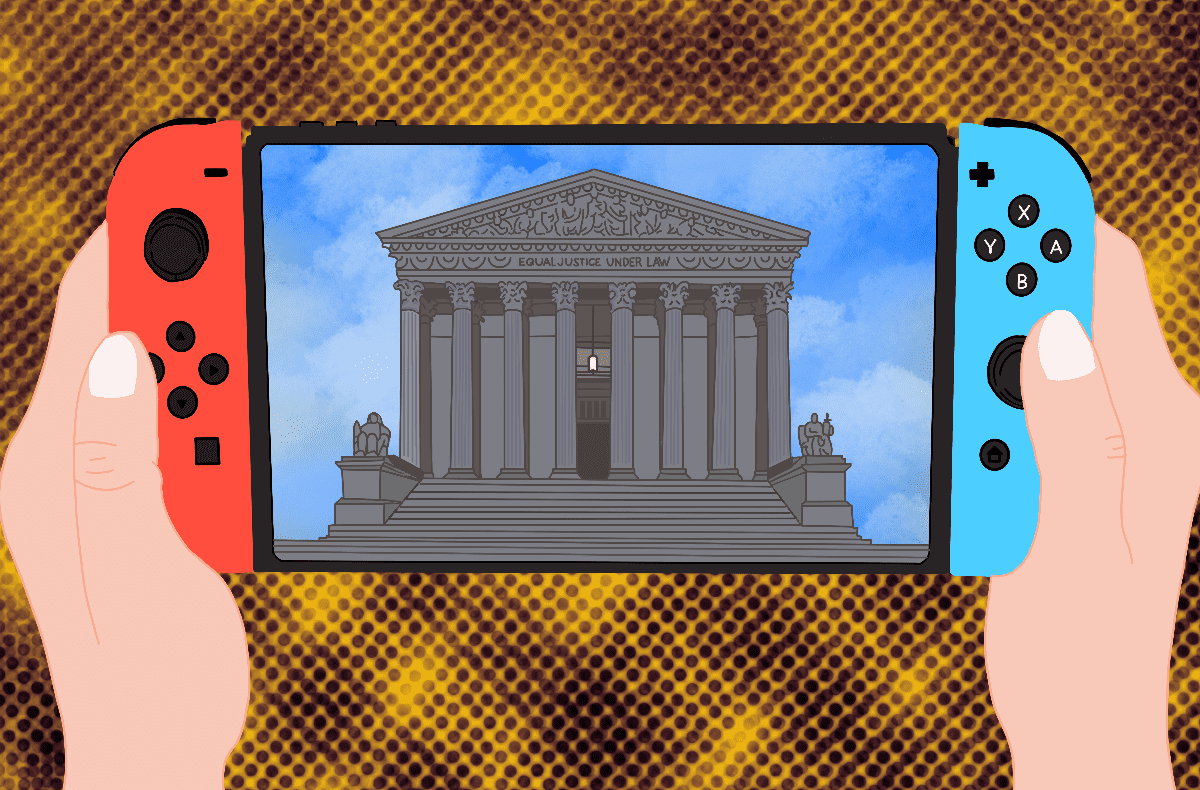

Video games could help turn the tide.

Following her 2006 retirement from the U.S. Supreme Court, Sandra Day O’Connor founded iCivics—a collection of games and other online resources for educators to reimagine civics education and re-engage students in the topic. The concept of teaching civics through gaming may seem hard to fathom, but these games have been played millions of times since iCivics launched in 2009. Freedom of speech is specifically addressed in the iCivics’ game, Do I Have a Right?, in which players attempt to grow the prestige and success of their own law firm specializing in constitutional law.

Good learning games situate the meaning of words by relating them to actions, images, and dialogue. In Do I Have a Right?, a player is presented with a potential client who shares a brief scenario, and the player has to determine not only if the client has a right under constitutional law but also if a lawyer in that practice has expertise in that particular aspect of an amendment. The game limits how many amendments are presented at the start and then ramps up over seven rounds. For example, the First Amendment is split between Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Assembly, and a lawyer in the player’s practice may be an expert in one, but not the other.

Adults are often wary of children playing too many games, treating them monolithically as frivolous and violent. O’Connor shared that view until she met James Paul Gee, a now-retired professor who paved the way for early research on how good video games are designed to enhance learning.

As a game designer and an assistant professor of games and design, I am passionate about the power of games to transform society. I direct a transdisciplinary design lab called Matters at Play, which focuses on how games can impact social justice, public health, and the environment. Educators and caregivers tasked with raising and shaping young people should consider the enormous potential of games, which can transform knowledge, awareness, and perspective on all sorts of societal issues.

Not sure where to start? iCivics provides professional development for educators and resources for families. Games for Change, a nonprofit exploring how the world can use games and immersive media for social good, also has a list of games in addition to hosting an annual festival that will mark 20 years of impact in 2023. Dr. Karen Schrier’s 2021 book, We the Gamers: How Games Teach Ethics and Civics is another valuable resource. Schrier shares considerations for how to choose the right game since a single game can show one aspect or perspective on an issue but does not need to—and arguably cannot—express all aspects.

For example, in 2012, I learned about a crucial immigration information gap for undocumented youth who find themselves in the custody of the U.S. government, often separated from and left without an adult guardian, and in removal proceedings to be legally required to leave the U.S. I designed Toma el Paso (Make a Move), a board game initially designed and implemented to help inform such minors about the shelter release process. The game has now been used in college-level courses on immigration to expand students’ awareness of the negative impact the U.S. immigration system has on unaccompanied immigrant minors in particular.

Twitter uproars come and go, but our understanding of freedom of speech—and civics more broadly—must prevail. With a curious and curated reliance on games, we can engage people of all ages in scenarios and lessons that will grow their understanding of and appreciation for their rights, hopefully encouraging them to make sure those rights are being protected and provided equally for all.