First time on a private jet. Cream leather seats, walnut veneer, the finest champagne: all oozing luxury and status. Her host was slim, good looking and impeccably dressed CEO of a diamond company, and—as his two hundred thousand Instagram followers testified—scion to an Israeli billionaire. She had feared perhaps arrogance and entitlement, but instead found only warmth, humour and generosity. Tellingly, his many—largely female—staff unanimously spoke of him with affection and gratitude. She could hardly believe she had met him on the dating app only the day before: his breathtaking spontaneity was part of the appeal. They had immediately formed a life-changing connection.

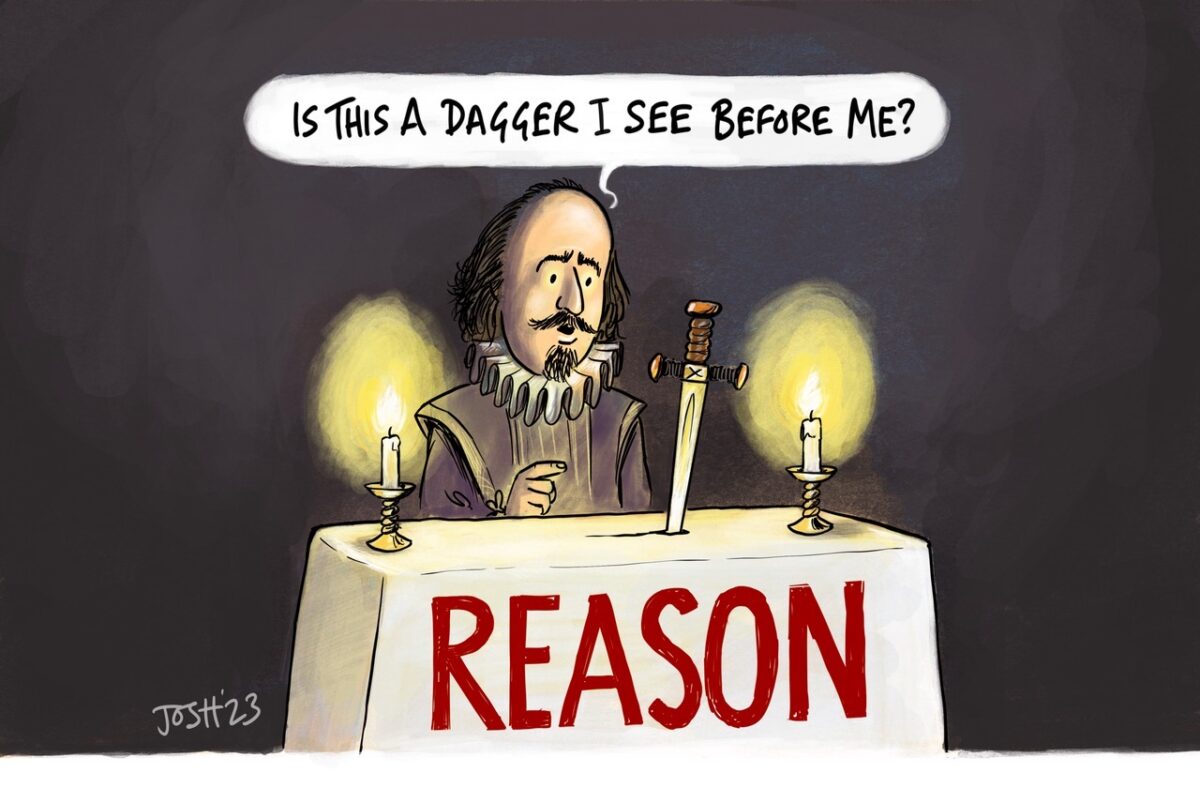

But as the then-29-year-old Norwegian Cecilie Fjellhøy was to discover many romantic and then terrifying weeks later, the devil hath power to assume a pleasing shape. Netflix’s trending true crime release The Tinder Swindler documents how Cecilie’s sociable, naturally trusting, and open nature had been completely taken in.

Who is at risk?

From the safety of one’s living room, it’s easy to write off Cecilie and fellow victims of Shimon Hayut (known to Cecilie as Simon Leviev) as gullible fools: how could anyone be so naïve? But the truth is: anyone can be conned. As with most crimes, victims can be of any age, any background, any educational attainment, any profession. The statistics speak for themselves. In Britain, fraud has now risen to such a level that it is considered a threat to national security. In the first half of 2021, UK fraud losses amounted to over £750 million, a 30% increase on the previous year. And as police resources become ever more stretched, many of these cases are not even investigated, let alone solved.

And of course, today’s fraud epidemic is in no small part due to the Internet. The opportunist fraudster can cast the criminal net so wide it is almost guaranteed to ensnare at least one victim, while the more selective conman can profile his potential targets via their online footprints with relative ease.

It is an almost risk-free crime. And can be very lucrative.

How is it done?

In the art of the con, knowledge is power.

What the successful scammer has above all is psychological acumen, often to an extraordinarily sophisticated degree. With a talent for assessing human needs and vulnerabilities, Hayut engaged in tactics to reduce his victims to a state of blind compliance. It was classic grooming behaviour.

First, he established credibility. For instance, he had an online profile that matched his purported life story: the Instagram followers in six figures. Those around him (who were complicit in the scam) provided validation and reassurance. Money was spent to create the illusion of a billionaire lifestyle: after all, perception can be manipulated. Whether in the physical world or online, words, behaviours, social structures and symbols or images all can be used as tools of theatre to engineer the conditions and sell us a lie. And once sold, we’re far more likely to act against our own interests.

Next, Hayut established an intense emotional connection. A surprise bouquet of red roses. Overnight stays in the finest hotels. Sensitive messages of concern over WhatsApp. Not least, the very impressive private jet deployed solely to meet his new flame. These were all calculated steps to create and deepen dependence. The human urge to reciprocate warmth and generosity is a powerful one—and readily exploited by grifters. It lowered his victims’ inhibitions and primed them to grant him unquestioning loyalty.

Finally, the manipulator creates distance from the usual support network. Sometimes by consuming so much attention, there’s simply no time for anyone else, other times the target is told secrecy is essential: whatever the approach, this isolates the victim from familiar sources of protection: friends; family; those who might question such a whirlwind romance followed by sudden urgent requests for money.

Win trust. Create dependence. Isolate the victim. Then in with the sting.

Hayut had laid the trail carefully. He had always suggested there were threats to his personal security: par for the course in the diamond trade, he claimed; and the reason for the imposing bodyguard. When the time was right, he would typically then tell his victims his life was in imminent danger and he needed immediate financial assistance: time-constraints are another classic giveaway, leaving no time for reflection or consideration. The response was preconditioned and immediate. Large money transfers followed.

How can we protect ourselves?

In cybersecurity, “Zero Trust” is a methodology that assumes everything is a threat until proven otherwise. It is the latest thinking to protect organisations from sophisticated adversaries.

But humans cannot live their lives in the same way. To go through life paranoid that everyone we encounter seeks to harm us would rob us of any experience worth having. As E.M. Forster wrote in Howard’s End, “it’s better to be fooled than to be suspicious.” Norwegian pop-band A-ha would reiterate the sentiment 75 years later, singing “it’s no better to be safe than sorry” in their smash hit, “Take On Me”! And, with most of our relationships, this is true. Most people are indeed trustworthy.

Nevertheless, we lock our front doors when we go out; we may even install CCTV or burglar alarms. This doesn’t mean we are irrationally neurotic or suspect everyone we pass in the street. It is simply an acknowledgement that burglary exists; and it can be very nasty. Nor does it mean we can’t possibly be burgled and our homes are 100% safe, just that we’ve done what we can to make a break-in less likely.

Similarly, it’s possible to retain our confidence in most of the people we meet and assume life is going to be good to us, whilst still putting in place some simple security measures to reduce the risk of losing our life’s savings or being subjected to traumatising cons.

By remembering these three simple guidelines, you can be less vulnerable:

- Verify strangers. Time was, when none of us trusted anyone without a personal introduction from someone we knew. Now, most of us meet at least some people for the first time without any acquaintances in common. We have to replace that security measure with something else. However credible the backstory seems, scrutinise it. A Google search is not enough, but the Internet is your friend. Learn some open source intelligence (OSINT) skills. Reverse search images (an essential OSINT trick) and look for independent corroboration of “facts” and dates. If the budget allows, seek professional help. As methodical as scammers are, there are nearly always indicators of concern to be detected if you probe their background thoroughly enough. Effective due diligence requires an objective, critical mindset. Do not simply seek to prove their story to be true; also try to disprove it. Always entertain the possibility that everything you are being told could be fabricated, until you have irrefutable and objective verification.

- Respect your instinct. Intuition is an innate protective force: we ignore it at our peril. If you have even the tiniest niggle, heed it. If some detail doesn’t seem to fit, don’t explain it away—however much you might want to. What the really clever con does is persuade us to persuade ourselves. The dream is so seductive: so much what we’ve always wanted. The fail-safe investment to solve all our money worries; the rich romantic lover to answer our loneliness. Belief is so much more attractive than doubt that we are highly motivated to overlook something not quite matching up. Don’t! Pause. Take time to consider. Could there be an alternative explanation? As the American security specialist Gavin de Becker tells us, intuition is “knowing without knowing why.”

- Never give money. Some cons can go on for years. Bigamists have been known to maintain two homes, two families, two marriages for decades before being uncovered. It is a good rule never to give money you can’t afford to lose, ever, even to the love of your life. Certainly not to someone you haven’t known for several years, lived with, shared a life with… and never, ever give money to someone you haven’t even or only recently met. Then, even if you are taken in, even if your heart is broken, even if you’ve been tricked and humiliated and abused and traumatised, at least your money is safe.

Ultimately, we all want to believe we wouldn’t succumb to a Hayut-style scam. But in truth, anyone can be conned. And if you believe you’ve never yet been deceived, you probably have.

You just don’t know it.