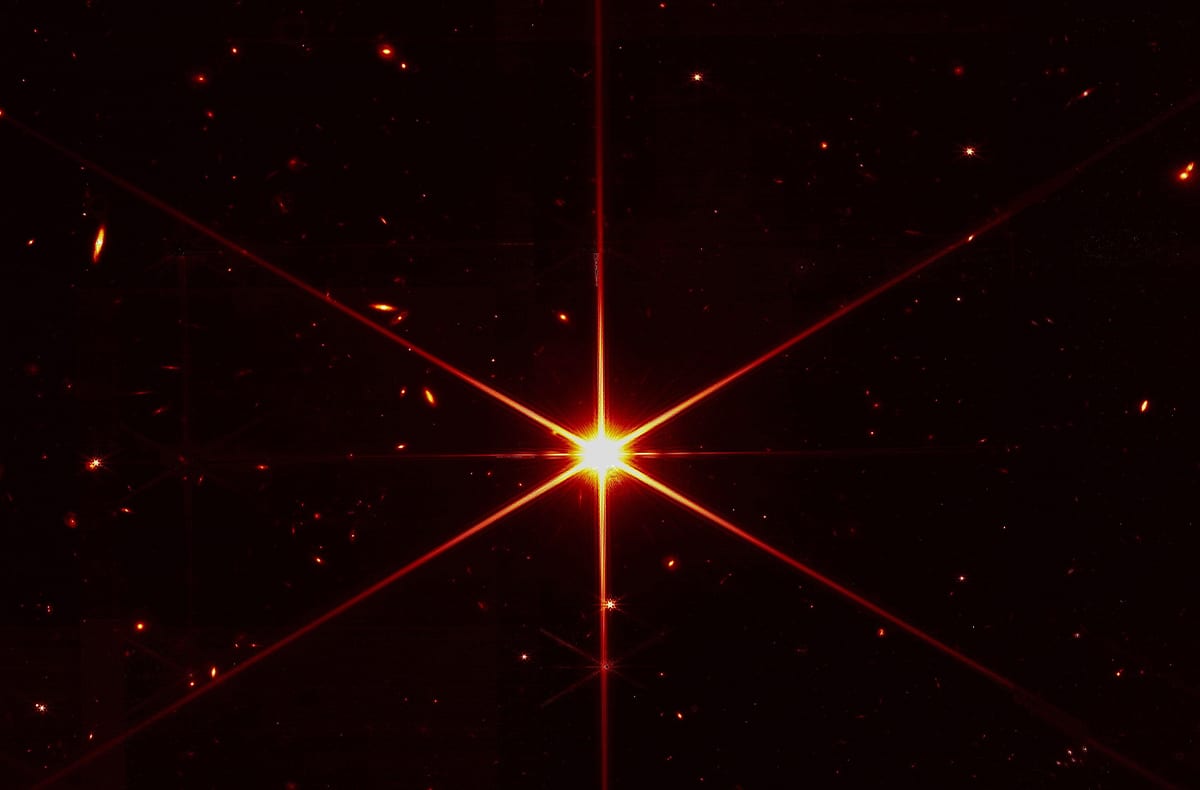

Eyes glazing over at the polycrisis unfolding across my many screens, I raise my sights to the stars. And for those (like me) who seek solace in the material cosmos—its mind-bending vastness and age, its potential for infinite variety—it’s been quite a few weeks.

I give praise to the beautiful, honeycombed mirrors of the James Webb Space Telescope (or JWST). Since the beginning of July, they have started receiving information about the universe never before gathered.

Out of a series of near-psychedelic images, the one that induced the most awe in me was the first released: a rectangle teeming with many thousands of galaxies. So momentous, it had to be ushered in by an American president (surely also looking for positive headlines before these ominous mid-term elections).

Nevertheless, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson caught the moment well. “This image covers a patch of sky approximately the size of a grain of sand, held at arm’s length. It’s just a tiny sliver of the vast universe…This mission was made possible by human ingenuity.”

I guess cosmology is my religion. It feels as true to the original etymology of the word—binding, reverence, obligation—as anything else I’ve known.

Binding, because I can’t imagine a wider and richer context in which my life and sentience has meaning. The titan of Protestantism, John Calvin, would have disagreed.

“If God had formed us of the stuff of the sun or the stars, or if he had created any other celestial matter out of which man could have been made, then we might have said that our beginning was honourable,” Calvin once wrote. “But we are all made of mud…We are full of it, we are nothing but mud and filth both inside and outside.”

But as eco-philosopher Theodore Roszak once noted, astrophysics tells us that we are, precisely, made of the hydrogen and carbon that also makes the “sun and the stars.” So cheer up (and clean up), Calvin. You actually are at home in the universe.

How does reverence fit with my cosmism? Well, I can think of nothing more deserving of awe than this tray of galactic material, gemstones scattered freely and generously on the velvet. The wellbeing experts tell us experiences that induce awe bring much value to our lives. By consoling us that we’re part of something bigger, they improve performance, tolerance, relationships.

I’ll be honest: some of my reverent awe at these cosmic sublimities is directed at the space scientists and engineers themselves. Their human smartness and precision makes the universe smaller, tractable and navigable (though that’ll more likely be a job for the mechas, than for we fleshbots, as the late James Lovelock predicted).

The obligation part of my cosmo-religiosity is maybe the most interesting bit. Perhaps I, you and we owe the material universe much more than we realise.

The British pop physicist Brian Cox laid it out pretty starkly this May. Life on Earth, ending up with smart apes like us, took something like a third of the whole period of the universe’s existence to occur. “That’s a long time…and that may indicate that microbes may be common, but things like us may be extremely rare.”

The JWST, orbiting a million miles out from Earth and with the clearest of views, is specifically designed to detect “biological signatures” from far-off planets. So we may soon meet with our microbial cousins in the cosmos.

But Cox’s words hold an implicit warning. If human civilisation is likely to be a precious thing in the universe, why are we trying to self-terminate—technologically, economically, ecologically, militarily?

Our obligation, then, is to strive for a sustainable and balanced earthly existence. One which can support the extension of a conscious civilisation throughout the universe, honouring its rarity.

It’s not that there aren’t Calvins in my cosmism. Physicist Enrico Fermi stated a famous paradox: if the universe is so unimaginably vast, why haven’t we encountered anyone else yet? His conclusion was grim: maybe they’re all like us. Meaning that they create powerful, world-shaping technologies, then put them in aggressive and competitive hands.

Fermi suggests these civilisations snuffed themselves out, in an exchange of weapons or a miasma of pollution, before they even started travelling to infinity and beyond. (This is cheerily known as “The Great Filter”). And that’s why it’s quiet as the grave out there.

I know: grim. But for me, this generates the most ambitious goal possible. Can we sapient ones beat this trap, defy this fatal arc, with our oh-so-rare capacity for imagination, invention and empathy? If we are as gods, as hippies like Stewart Brand used to say, can we get good at it?

It’s why the interplanetary Elon Musk always gets one minimal cheer in our house (he recently tweeted about a “philosophy of the future” based on space exploration). Though I would like this cosmos-oriented civilisation to be a lot more Trekkie, wearing bureaucratic jumpsuits, than defined by some toking Marspreneur. Unsurprisingly, I’m pleased that the James Webb has been a lengthy and calm co-production between NASA and the European and Canadian Space Agencies.

But the Space Telescope is only getting started up there: many more grains of sand will be held up to the sky in the coming years. Maybe if we gaze at them for long enough, we’ll come back renewed to the faces and forces around us. With our inner space a little more capacious and sagacious.