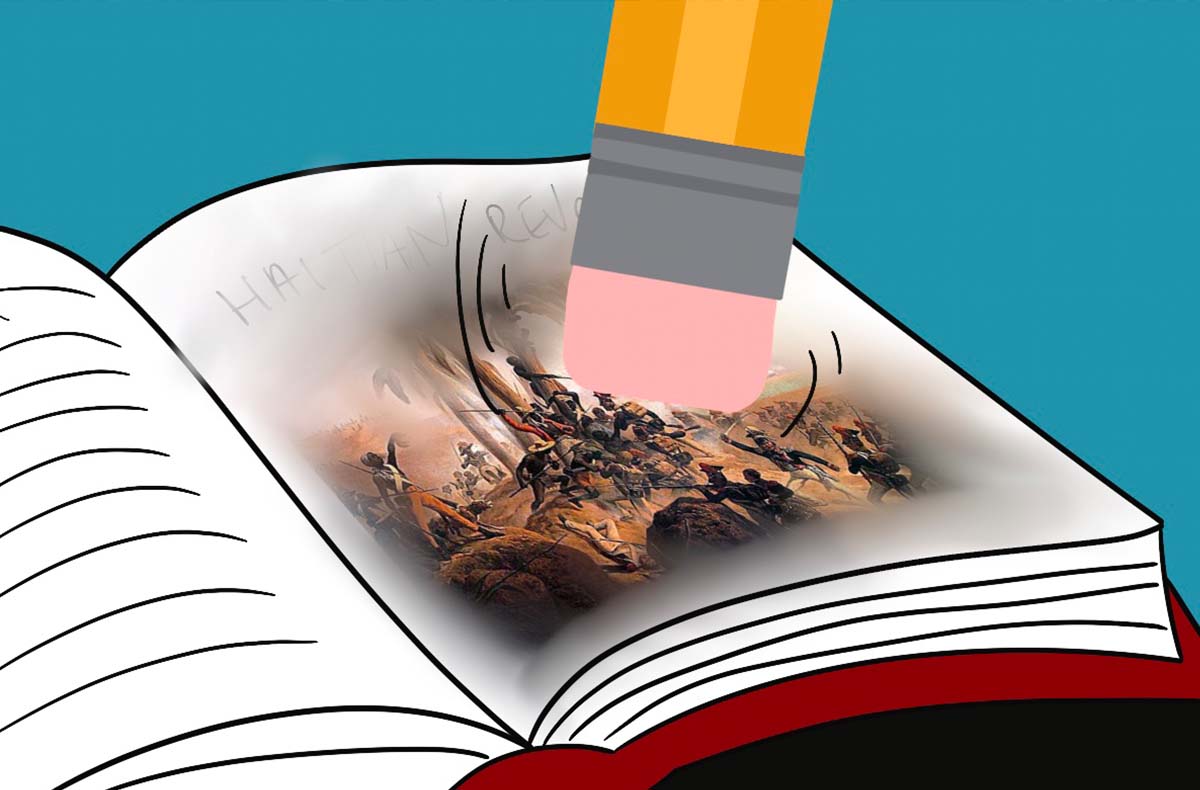

Image by Nikki Muller

In the United States, what students learn—or don’t learn—about race at school has become one of the most fiercely contested fronts of the culture wars. Government bans on teaching Black history are increasingly common and draconian, supposedly in response to the overreaches of “critical race theory” proponents. The current crackdown is the culmination of a campaign launched by right-wing activist Christopher Rufo, who deemed critical race theory (a famously flexible term in the hands of conservatives) “the perfect villain” on which to pin the country’s ongoing existential crisis.

The main argument, which Rufo and conservative media figures from Tucker Carlson to Candace Owens broadcast to the world on an almost daily basis, boils down to this: students are being forced to view our collective history through a distorted lens, which prevents them from understanding the world and has severe negative consequences for both individuals and society at large.

That sounds bad, indeed. It also describes the experience that I (and many others) had in history class long before “CRT” was an acronym anyone outside of academia would recognize. The case of Haiti is a prime example.

I spent most of my childhood attending good-quality public schools in the Minnesotan suburbs, and in all my history classes, slavery in the Americas received more attention than any other topic. We learned about the horrors of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the brutality of cotton and sugar plantations, and the heroic efforts of abolitionists from Frederick Douglass to Sojourner Truth to John Brown.

Going back further, we learned that the Spanish colonists were particularly brutal enslavers (the British and French were certainly no saints, according to the textbooks, but their rational economic interests at least tempered their cruelty). We learned that, while slavery had existed in other places and other times throughout history, the version of it practiced in the New World was uniquely exploitative and cruel.

Yet through all of this, we never spent more than a few moments talking about Haiti.

This was surprising to me because when Haiti was mentioned in the textbooks, it seemed like a hugely important story. The Haitian Revolution was the biggest uprising by enslaved people since Spartacus’ revolt against the Romans nearly two millennia prior—and this one was successful.

Roughly 70 years before the American Civil War, Black people on an island about two hours’ flight from Miami had not only liberated themselves from their enslavers, but gone on to found their own independent state. “Surely that must’ve had some ripple effects in the United States and beyond,” I thought. But if it did, we didn’t learn about it in class.

A seemingly reasonable answer exists for this: the post-independence history of Haiti isn’t a cheerful one.

In 2022, the New York Times published a massive investigation titled “The Ransom” that sought to explain why Haiti has been one of the poorest and most unstable countries in the world since its founding.

In typical Times fashion, it features plenty of references to Haiti’s internal corruption and self-created problems, but the tepid both-sides-ism is belied by the bulk of the report. One installment, called “The Roots of Haiti’s Misery: Reparations to Enslavers,” explained how France literally forced the country at gunpoint to repay at least $21 billion USD (in today’s terms) to former slave owners.

Since Haiti obviously didn’t have that kind of cash on hand, it was forced to borrow from foreign lenders—particularly those in France and the United States. Some of the bounty went to finance the Eiffel Tower; some of it went into the pockets of American banks like Citigroup’s predecessor. As usual, a “helping hand” from the international monetary system was contingent on cutting social services to the bone.

Predictably, this begot poverty and desperation, which begot chaos, which begot a U.S. military occupation from 1914-1935. During this period, according to the Times, “more of Haiti’s budget went to paying the salaries and expenses of the American officials who controlled its finances than to providing healthcare to the entire nation of around two million people.”

Needless to say, we didn’t learn any of that at school in the late 1990s and early 2000s. And despite the hand wringing about the pervasiveness of CRT in contemporary U.S. education, not much has changed since then.

For despite the right-wing accusations that “neo-Marxist race-baiting propaganda merchants” have taken over U.S. education, the people in charge of the system remain deeply committed to ensuring that nothing fundamentally changes, as Joe Biden once promised.

They’re not stupid: especially in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd uprisings, they recognize the need to appear more diverse and inclusive. Hence (some) schools’ interest in featuring more books by Black authors, and the recent spike in funding for HBCUs, historically Black colleges and universities.

But if teachers still can’t talk about the most important uprising of enslaved people in modern history, or explain how yesterday’s slavery provided the seed money for today’s capitalism, then the laments of those who claim students are being fed a distorted version of U.S. history will continue to ring true—just in the opposite way they intended.